|

Heinkel HE 100

On the 30th of March 1939

a prototype of the new Heinkel He 100 fighter design streaked into the

record books at 746.6km/h — the new world absolute speed record.

Surprisingly it took the record away from a plane with well over twice the

horsepower, and beat it by over 40km/h. Lessons learned from earlier

Heinkel projects had been put to good use and its advanced aerodynamics

resulted in a plane that was the best performing fighter in the air, even

in its less slippery production line model.

Little information on the

plane is available, and what there is often contradictory. All we know for

sure is that Heinkel built the world's fastest plane, and it was suitable

for use as a fighter (unlike many racing planes). We also know that after

being built and proving itself in testing, the production line only built

twelve planes before shutting down. The rest of the He 100 story is

clouded in mystery, which makes it all the more interesting.

Basic specifications

|

Company: |

Ernst Heinkel

Flugzeugwerke GmbH |

|

Designer: |

Walter and Siegfried

Günther |

|

Year:

|

1938 |

|

Type:

|

Single seat day fighter

|

|

Description: |

Low wing monoplane

fighter with conventional control surface layout. |

|

Fuselage: |

Egg shaped cross section

with flattened sides, particularly around the engine. The front of the

plane is largely flat horizontally, sloping down sharply behind the

spinner. The rear of the plane slopes down toward the rear, starting at

a high point at eye level behind the cockpit and ending up roughly level

with the bottom of the canopy at the tail. |

|

Wings:

|

The wings are largely

rectangular, with rounded tips. The inner portion of the wing is flat on

the bottom and then bends up about 1/3rd along the span, but due to the

thinning of the wing it appears to have a slight reverse gull-wing bend.

The portion inboard of the bend is thicker with parallel leading and

trailing edges, outside of the bend the leading edge tapers back

slightly, and the trailing edge forward more strongly. Flaps span the

area inside of the bend, and ailerons start at the half way point and

run to the tips. |

|

Other

details: |

The canopy is similar to

the Malcolm hood from later Spitfires, in which a rounded center section

slides to the rear over smaller windows set into the fuselage. The

windscreen at the front is well rounded and the flat plate in front of

the gunsight is small and well faired. Fully retractable tail–dragger

landing gear were used, with the main gear retracting inward towards the

fuselage, the wheels laying in the thick inner portion of the wing.

|

Background

The Heinkel He 100 story

starts in 1933 with the Reichsluftsfahrtministerium

(Reich Air Ministry, or RLM) competition to

produce the first modern fighter for the re-forming

Luftwaffe. Four designs were submitted; Arado's Ar 80, Focke–Wulf's

Fw 159, Heinkel's He 112 and the Messerschmitt Bf 109. All four planes

were tested competitively in early 1936 with interim engines, and the Ar

80 and Fw 159 were quickly eliminated. Both the 112 and 109 were

considered worthy of further testing, and orders were sent out for 15

additional aircraft from both companies.

Although Heinkel was

considered the favorite to win the contract, the more modern and better

performing 109 won over the Flight Acceptance Commission. By late March of

1936 the 109 was considered the favorite. At that point Heinkel was

allowed to redesign the 112, which resulted in the largely all–new 112B.

The 112B was considerably improved and was as good or better than the 109,

but the 109 won anyway.

The 112 had a few problems

that lost it the competition. The first was that the airframe was rather

complex; it included a large number of compound curves and its elliptical

wing was labor intensive. The RLM was looking

to produced hundreds of planes, so cost in both dollars and manhours was a

factor. The prototypes also suffered from a series of accidents, even if

they weren't related to problems with the plane they still left a bad

taste in the mouth.

But the biggest problem

for the 112 was that after learning that Supermarine had started series

production of the Spitfire, the Luftwaffe was

desperate to get a modern fighter into squadron hands. Heinkel might have

won the competition had the B model been available in early 1936, but by

the time they were ready in the second half of the year the 109 was

already in series production.

Nevertheless some small

scale contracts for the plane were finally secured with a variety of air

forces in Europe and Japan. Thirty were bought by Japan, but twelve of

these were used briefly by the Luftwaffe during the

Sudetenland Crisis. Another nineteen were then sold to Spain where they

served long careers. Thirty were sold to Romania, they served in combat in

1941 but were quickly worn out. Finally three more B's were sold to

Hungary as the vanguard of a license production series that never took

place.

By 1939 production of the

He 112 ended, and it appeared that Heinkel was out of the fighter

business.

Development history

Even by early 1936 the

RLM became interested in a new fighter that

would leap beyond the performance of the Bf 109 as much as the 109 had

over the biplanes it replaced. There was never an official project on the

part of the RLM, but Roluf Lucht felt that

new designs were important enough to ask both Focke–Wulf and Heinkel to

provide "super–pursuit" designs for evaluation.

Since the super–pursuit

type was not an official recommendation, it was possible that Heinkel

would be told to stop work on the project. Thus the work was kept secret,

in a company Memo No.3657 on January 31st this was made clear; "The mockup

is to be completed by us... as of the beginning of May... and be ready to

present to the RLM... and prior to that no

one at the RLMis to know of the existence of

the mockup."

Walter Günter —one of

Heinkel's most talented designers— looked at the 112 and decided that

nothing more could be done with it. He started over with a completely new

design known as "Projekt

1035". Learning from past mistakes on the 112 project, the design was to

be as easy to build as possible while still offering good performance.

That good performance was set at an astounding 700km/h (435mph). Keep in

mind that fighters with this sort of performance didn't appear on the

battlefield until 1944.

To ease production the new

design had considerably fewer parts than the 112, and those that remained

contained considerably few compound curves. In part count the 100 was made

of 969 unique parts and was held together with 11543 rivets, in comparison

the 112 had 2885 parts and 26864 rivets. The new straight-edged wing was a

source of much of the savings, after building the first wings Otto Butter

reported that the reduction in complexity and rivet count (along with the

Butter brothers's own explosive rivet system) saved an astonishing 1150

man hours per wing.

In order to get the

promised performance out of the plane, the design included a number of

drag reducing features. On the simple end was a well–faired cockpit, the

absence of struts and other draggy supports on the tail, and fully

retractable gear (including the tailwheel) which were completely enclosed

in flight. These and similar changes applied to the 109 for the F model

would boost performance of that plane 50km/h. The engine was mounted

directly to a strong forward fuselage as opposed to internal struts, so

the cowling was very tight fitting and as a result the plane has something

of a slab sided appearance. The design used a shorter wing than the 109,

trading altitude and turn performance for speed.

In order to provide as

much power as possible from the DB 601 engine, the 100 used exhaust

ejectors for a small amount of additional thrust. In addition the

supercharger inlet was moved from the normal position on the side of the

cowling to a location in the leading edge of the left wing, where the

clean airflow improved the ram-air effect and increased boost.

For the rest of the

designed performance increase, Walter turned to the risky method of

cooling the engine via surface evaporation. Inside the engine the fluid is

kept under pressure which stops it from boiling even though it's allowed

to heat above its normal boiling point, the fluid is then run to cavity

with lower pressure where it quickly starts to boil and releases steam.

Since steam contains considerably more energy than the same temperature

water, if you can remove the steam you can remove a lot of heat. The

stream can be cooled by allowing it to condense in a series of pipes

inside the plane. With no external openings at all, it's basically a

zero-drag cooling system.

On the down side the

system is complex and hard to maintain. Worse, it greatly increases the

chance of killing the engine in combat due to a "radiator hit" on the now

much larger cooling system. Other designs would attempt to use the same

sort of design, but invariably returned to conventional radiators due to

the complexity. A number of people had already tried the system and given

up on it, but Heinkel had good experiences with it on their He 119 high

speed bomber project and decided to press ahead.

In the Heinkel system

—designed by Jahn and Jahnke— the engine was run at 110 Celsius and the

superheated fluid was then sprayed into the interior of a centrifugal

compressor, allowing the pressure to drop and steam to form. The water,

being heavier, was forced to the outside of the pump by centrifugal force

and returned to the engine. The weight of the water forced the steam into

the only available space, the inside of the pump, where it was removed.

The steam was then allowed to flow into a series of tubes running on the

inside surface of the leading edges of the wings, where it would condense

back into water and be pumped back to the engine. A number of pumping

systems were tried, and eventually a system of no less than 22 small

electric pumps (all with their own failure indicator lamp in the cockpit)

was settled on.

Unlike the cooling fluid,

oil cannot be allowed to boil. This presents a particular problem with the

DB 601 series of engines, because of a particular design technique that

results in a considerable amount of heat being transfered to the oil as

opposed to the coolant. To cool the oil a small semi-retractible radiator

was fitted under the wing.

This radiator was later

replaced on some of the prototypes with a system in which the oil was sent

to a heat exchanger where it boiled methyl alcohol to carry away the heat.

The alcohol was then cooled in a similar fashion to the engine fluid, by

running it to tubes on the top surface of the rear fuselage and leading

edge of the vertical stabilizer.

Walter was killed in a car

accident on May 25th, 1937, and the design work was taken over by his twin

brother Siegfried, who finished the final draft of the design later that

year. The wing started out flat and then bent upwards about 1/3rd along

the span, and the portions inboard of the bend were thicker to hold the

wheels. The gear retracted inward and thus were wide set when opened,

resulting in a significant improvement in ground handling over the 109.

The rear of the fuselage sloped down to the tail from a point at about eye

level at the rear of the cockpit, so while it didn't have the visibility

of the 112's bubble, it was still significantly better than the 109. A

small retractable radiator was added for running on the ground where the

surface cooling system wouldn't work. The plane was small, slightly

smaller than the 112 that spawned it, and considerably lighter.

At the end of October the

design was submitted to the RLM, complete

with details on prototypes, delivery dates, and prices for three planes

delivered to the Rechlin test center. At this point the plane was being

referred to as the He 113, but the "13" in the name was apparently enough

to prompt Ernst Heinkel to ask for it to be changed to the He 100 (even

though it had previously been given to Feiseler).

In November Messerschmitt

took the speed record for landplanes in a modified 109. In response Ernst

Heinkel made plans to use the He 100 design as a record setting plane

(less serious plans for this appear to have been in the works all along).

Much of the fuselage was as smooth as it could get, so the modifications

were limited to the canopy and a newer set of much shorter wings. The

racing version would need another airframe, so a fourth prototype was

added to the series.

In a December meeting at

the Heinkel factory with Ernst Udet and Roluf Lucht the plans were changed

slightly. V1 through V3 were to be used for testing and record attempts,

V3 sporting the clipped wings. V4 was to a testbed for series production.

The RLM went ahead with the plan, due in no

small part to Udet's (Generalluftzeugmeister,

Minister for Aircraft Production in the RLM)

plans to fly the plane in a series of record attempts.

Prototypes

The first prototype He 100

V1 flew on January 22nd, 1938, only a week after it's promised delivery

date. The plane proved to be outstandingly fast. However it continued to

share a number of problems with the 112, notably a lack of directional

stability. In addition the Luftwaffe test pilots disliked the high wing

loading, which resulted in landing speeds so great that they often had to

use breaks right up to the last 100m of the runway. The ground crews

disliked the design too, complaining about the tight cowling which made

servicing the engine difficult. But the big problem turned out to be the

cooling system, largely to no one's surprise. After a series of test

flights V1 was sent to Rechlin in March.

The second prototype

addressed the stability problems by changing the vertical stabilizer from

a triangular form to a larger and more rectangular form. The oil cooling

system continued to be problematic so it was removed and replaced with a

small semi-retractible radiator below the wing. It also received the

still–experimental DB 601M engine which the plane was originally designed

for. The M version was modified to run on "C3" fuel at 96 octane, which

would allow it to run at higher power ratings in the future.

V2 was completed in March,

but instead of moving to Rechlin it was kept at the factory for an attempt

on the 100km closed-circuit speed record. A course was marked out on the

Baltic coast between Wustrow and Müritz, 50km apart, and the attempt was

to be made at the plane's best altitude of 18000ft. After some time

cleaning out the bugs the record attempt was set to be flown by Captain

Herting, who had previously flown the plane serveral times. At this point

Ernst Udet showed up and asked to fly V2, after pointing out he had flown

the V1 at Rechlin. He took over from Hertingand flew the V2 to a new world

100km closed circuit record on the 5th of June, 1938, at 634.73km/h

(394.6mph). Several of the cooling pumps failed on this flight as well,

but Udet wasn't sure what the lights meant and simply ignored them.

The record was heavily

publicized, but in the press the plane was referred to as the "He 112U".

Apparently the "U" stands for "Udet". At the time the 112 was still in

production and looking for customers, so this was one way to boost sales

of the older design. V2 was then moved to Rechlin for continued testing.

Later in October the plane was damaged on landing when the tail wheel

didn't extend, and it's unclear if the damage was repaired.

The V3 prototype received

the clipped racing wings, which reduced span and area from 30ft 10in and

155sq ft, to 24ft 11in and 118.4sq ft. The canopy was replaced with a much

smaller and more rounded version, and all of the bumps and joints were

puttied over and sanded down. The plane was equipped with the 601M and

flown at the factory.

In August the DB 601R

engine arrived from Daimler-Benz and was installed. This version increased

the maximum RPM from 2200 to 3000, and added methyl alcohol to the fuel

mixture to improve cooling in the supercharger and thus increase boost. As

a result the output was boosted to 1776hp, although it required constant

maintenance and the fuel had to be drained completely after every flight.

The plane was then moved to Warnemünde for the record attempt in

September.

On one of the pre-record

test flights by the Heinkel chief pilot, Gerhard Nitschke, the main gear

failed to extend and ended up stuck half open. Seeing as the plane could

not be safely landed it was decided to have Nitschke bail out and let the

plane crash in a safe spot on the airfield. Gerhard was injured when he

hit the tail on the way out, and made no further record attempts.

V4 was to have been the

only "production" prototype and was referred to as the "100B" model (V1

through V3 being "A" models). It was completed in the summer and delivered

to Rechlin, so it wasn't available for modification into racing trim when

V3 crashed. Although the plane was unarmed it was otherwise a service

model with the 601M, and in testing over the summer it proved to be

considerably faster than the 109. At sea level the plane could reach

348mph, faster than the 109E's speed at its best altitude! At 6560ft it

improved to 379mph, topping out at 416mph at 16400ft before falling again

to 398mph at 26250ft. The plane had flown a number of times before its

landing gear collapsed while standing on the pad on the 22nd of October.

The plane was later rebuilt and flying by March of 1939.

Although V4 was to have

been the last of the prototypes in the original plans, production was

allowed to continue with a new series of six planes. One of the airframes

was selected to replace V3, and as luck would have it V8 was at the "right

point" in its construction and was completed out of turn. It first flew on

the 1st of December, but this was with a standard DB 601Aa engine. The

601R was then put in the plane on the 8th of January 1939, and moved to a

new course at Oranienberg. After several shakedown flights, Hans Dieterle

flew to a new record on March 30th, 1939, at 746.6km/h (463.9mph). Once

again the plane was referred to as the He 112U in the press. It's unclear

when happened to V8 in the end, it may have been used for crash testing.

V5 was completed like V4,

and first flew on November 16th. It was later used in a film about V8's

record attempt, in order to protect the record breaking plane. At this

point a number of changes were made to the design resulting in the "100C"

model, and with the exception of V8 the rest of the prototypes were all

delivered as the C standard.

V6 was first flown in

February 1939, and after some test flights at the factory it was flown to

Rechlin on the 25th of April. There it spent most of its time as an engine

test-bed. On the 9th of June the gear failed in-flight, but the pilot

managed to land the plane with little damage and it was returned to flying

condition in six days.

V7 was completed on the

24th of May with a change to the oil cooling system. It was the first to

be delivered with armament, consisting of two 20mm MG/FF in the wings and

four 7.92mm MG17's arranged around the engine cowling. This made the 100

the most heavily armed fighter of its day. V7 was then flown to Rechlin

where the armament was removed and the plane was used for a series of high

speed test flights.

V9 was also completed and

armed, but was used solely for crash testing and was "tested to

destruction". V10 was originally to suffer a similar fate, but instead

ended up being given the racing wings and canopy of the V8 and displayed

in the German Museum in Munich as the record–setting "He 112U". It was

later destroyed in a bombing attack.

Overheating problems and

general failures with the cooling system motors continued to be a problem.

Throughout the testing period failures of the pumps ended flights early,

although some of the test pilots simply starting ignoring them. In March

Kleinemeyer wrote a memo to Ernst Heinkel about the continuing problems,

stating that Schwärzler had asked to be put on the problem.

Another problem that was

never cured during the prototype stage was a rash of landing gear

problems. Although the wide-set gear should have eliminated the gear

failures that plagued the 109, the 100's were built very thin and as a

result they were no improvement. V2, 3, 4, and 6 were all damaged to

various degrees due to various gear failures, a full half of the

prototypes.

He 100D-0

Throughout the prototype

period the various models were given series designations (as noted above),

and presented to the RLM as the basis for

series production. The Luftwaffe never took them up on the offer. Heinkel

had decided to build a total of 25 of the planes one way or the other, so

with 10 down there were another 15 of the latest model to go. In keeping

with general practice, any series production is started with a limited run

of "zero-series" machines, and this resulted in the He 100D-0.

The D-0 was similar to the

earlier C models, with a few notable changes. Primary among these was a

larger vertical tail in order to finally solve the stability issues. In

addition the cockpit and canopy were slightly redesigned, with the pilot

sitting high in a large canopy with excellent vision in all directions.

The armament was reduced from the C model to one 20mm MG/FF-M in the

engine V firing through the propeller spinner, and two 7.92mm MG17's in

the wings close to the fuselage.

The three D-0 planes were

completed by the summer of 1939 and stayed at the Heinkel Marienehe plant

for testing.

He 100D-1

The final evolution of the

short He 100 history is the D-1 model. As the name suggests the design was

supposed to be very similar to the pre-production D-0's, the main planned

change was to enlarge the horizontal stabilizer

But the big change was the

eventual abandonment of the surface cooling system, which proved to be too

complex and failure prone. Instead an even larger version of the

retractable radiator was installed, and this appeared to completely cure

the problems. The radiator was inserted in a "plug" below the cockpit, and

as a result the wings were widened slightly.

While the plane didn't

match it's design goal of 700km/h once it was loaded down with weapons,

the larger canopy and the radiator, it was still capable of speeds in the

400mph range. A low drag airframe is good for both speed and range, and as

a result the He 100 had a combat radius between 900 and 1000km compared to

the 109's 600km. While not in the same league as the later escort

fighters, this was at the time a superb range and may have offset the need

for the 110 to some degree.

By this point the war was

underway, and as the Luftwaffe would not purchase the plane in its current

form, the production line was shut down.

Specifications for the He

100D-1c

|

Engine: |

1,175hp (876kW)

Daimler-Benz DB 601M liquid–cooled inverted V12 |

|

Dimensions: |

span 9.42m (30ft 10

3/4in)

length 8.20m (26ft 10 3/4in)

height 3.60m (11ft 9 3/4 in) |

|

Weights: |

empty 2070kg (4,563lb)

max loaded 2500kg (5,512lb) |

|

Wing

Area: |

14.5m2

(156ft2)

|

|

Wing

Loading: |

29.25lbs/ft2

|

|

Performance: |

maximum speed 668km/h at

6400m (416mph at 21,000ft)

560km/h (348mph) at sea level

cruise speed unknown

service ceiling 11000m (36,090ft)

range 900km (559miles) |

|

Armament: |

one 20mm MG/FF-M firing

through the propeller spinner

two 7.92mm MG17 in the wings |

He 100 in service

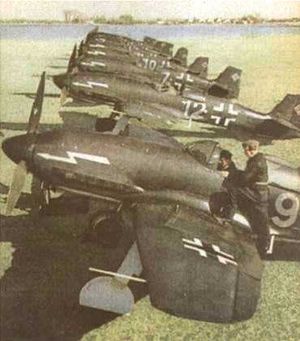

In 1940 the He 100's were

publicized by Goebbels in a propaganda effort aimed at convincing people

that a new fighter was entering service with the Luftwaffe. The plan

involved taking pictures of the remaining D-1's at different air bases

around Germany, each time sporting a new paint job for various fictional

fighter groups. The pictures were then published in the press with the He

113 name, sometimes billed as night fighters (rather silly since you could

see they didn't even have a landing light).

The plane also appeared in

a series of "action shot" photographs in various magazines like

Der Alder, including claims that it had proven

itself in combat in Denmark and Norway. One source claims that the planes

were on loan to the one Luftwaffe staffel in Norway for a time, but this

might be a case of the same misinformation working many years later.

It's unclear even today

exactly who this effort was intended to impress —foreign air forces or

Germany's public— but it seems to have been a successful deception.

British intelligence featured the plane in AIR 40/237, a report on the

Luftwaffe that was completed in 1940. There the top speed was listed as

390mph (interesting that it also states the wing was 167 square feet) and

it noted that the plane was in production. Reports of 113's encountered

and shot down were listed throughout the early years of the war.

The remaining twelve He

100D-1c fighters were used to form Heinkel's Marienehe factory defense

unit, flown by factory test pilots. They replaced the earlier He 112's

that were used for the same purpose, and the 112's were later sold off. At

this early stage in the war there were no bombers venturing that far into

Germany, and it appears that the unit never saw action. The eventual fate

of the D-1's remains unknown.

Foreign use

When the war opened in

1939 Heinkel was allowed to look for foreign licensees for the design.

Japanese and Soviet delegations visited the Marienehe factory in late

October, and were both impressed with what they saw. Thus it was in

foreign hands that the 100 finally saw use, although only in terms of

adopted design features.

The Soviets were

particularly interested in the surface cooling system, and in order to

gain experience with it they purchased the six surviving prototypes (V1,

V2, V4, V5, V6 and V7). After arriving in the USSR they were passed onto

the ZAGI institute for study, there they were analyzed and its features

influenced a number of Soviet designs, notably the LaGG-3. Although the

surface cooling system wasn't copied, the addition of larger Soviet

engines made up for the difference and the LaGG-3 was a reasonably good

performer. It's perhaps ironic that German planes would later be shot down

by German inspired planes.

The Japanese were also

looking for new designs, notably those using inline engines where they had

little experience. They purchased the three D-0's for 1.2 million DM, as

well as a license for production and a set of jigs for another 1.8 million

DM. The three D-0's arrived in Japan in May 1940 and were re-assembled at

Kasumigaura. They were then delivered to the Japanese Naval Air Force

where they were re-named AXHei, for "Experimental Heinkel Fighter". When

referring to the German design the plane is called both the He 100 and He

113, with at least one set of plans bearing the later name.

In tests the Navy was so

impressed that they planned to put the plane into production as soon as

possible as their land-based interceptor — unlike every other forces in

the world, the Army and Navy both fielded complete land-based air forces.

Hitachi won the contract for the plane and started construction of a

factory in Chiba for its production. With the war in full swing in Europe

however, the jigs and plans never arrived. Why this wasn't sorted out is

something of a mystery, and it appears there isn't enough information in

the common sources to say for sure what happened.

The DB 601 engine design

was far more advanced than any indigenous Japanese design, which tended to

concentrate on air cooled radials. To get a jump into the inline field,

Kawasaki had already purchased the license for the 601A from Daimler Benz

in 1938. The adoption process went smoothly, they adapted it to Japanese

tooling and had it in production by late 1940 as the Ha-40.

At the same time Kawasaki

was working on two parallel fighter efforts, the Ki-60 heavy fighter and

the Ki-61. The former was abandoned after poor test results (the test

pilots disliked the high wing loading, as they always did) but work

continued on the lightened Ki-61 with the Ha-40 engine. The Ki-61 was

clearly influenced by the He 100.

Like the D's it lost the

surface cooling system (although an early prototype may have included it),

but is otherwise largely similar in design except for changes to the wing

and vertical stabilizer. Since the Ki-61 was supposed to be lighter and

offer better range than the Ki-60, the design had a longer and more

tapered wing for better altitude performance. This also improved the

handling to the delight of the test pilots, and the plane was put into

production. The Hien would prove to be the first of the Japanese planes

that was truly equal to the contemporary US fighters.

Further developments

In late 1944 the

RLM went shopping for a new high altitude

fighter with excellent performance. It's unclear exactly why this

happened, as the Ta 152H version of the Fw 190 was currently in limited

production for just this task. Nevertheless Heinkel was contracted to

design such a plane, and Siegfried Günter was placed in charge of the new

"Projekt 1076".

The resulting design was

similar to the He 100, but many detail changes resulted in a plane that

looked all-new. It sported a new and longer wing for high altitude work,

which lost the gull-wing bend and was swept forward slightly at eight

degrees. Flaps or ailerons spanned the entire trailing edge of the wing

giving it a rather modern appearance. The cockpit was pressurized for high

altitude flying, and covered with a small bubble canopy that was hinged to

the side instead of sliding to the rear. Other changes that seem odd in

retrospect is that the gear now retracted outward like the original 109,

and he re-introduced the surface cooling system. Planned armament was one

30mm MK 103 cannon firing through the propeller hub, and two wing-mounted

30mm MK 108 cannons.

The use of one of three

different engines was planned: the DB 603M with 1825hp, the DB 603N with

2750hp or the Jumo 213E with 1750hp (the 603M and 213E both supplied

2100hp using MW-50 water injection). Performance with the 603N was

projected to be a shocking 880km/h (546mph), which would have stood as a

record for many years even when faced with dedicated racing machines.

Performance would still be excellent even with the far more likely 2000hp

class engines, the 603M was projected to give it the equally amazing speed

of 855km/h (532mph).

These figures are somewhat

suspect though, and are likely just optimistic guesses that could not have

been met — something Heinkel was famous for. Propellers loose efficiency

as they approach the speed of sound, and eventually they no longer provide

an increase in thrust for an increase in engine power. Even the advanced

counter-rotating VDM design is unlikely to have been able to effect this

problem too much.

The design apparently

received low priority, and it was not completed by the end of the war.

Siegfried Günter later completed the detailed drawings and plans for the

Americans in mid-1945.

Conclusions

In 1939 the He 100 was

clearly the most advanced fighter in the world. It was even faster than

the Fw 190, and wouldn't be bested until the introduction of the F4U in

1943. Nevertheless the plane was not ordered into production. The reason

the He 100 wasn't put into service seems to vary depending on the person

telling the story, and picking any one version results in a firestorm of

protest.

Some say it was politics

that killed the He 100. However this seems to stem primarily from

Heinkel's own telling of the story, which in turn seems to be based on

some general malaise over the He 112 debacle. The fact is that Heinkel was

well respected within the establishment regardless of Messerschmitt's

success with the 109 and 110, and this argument seems particularly weak.

Others blame the bizarre

production line philosophy of the RLM, which

valued huge numbers of single designs over a mix of different planes. This

too seems somewhat suspect considering that the Fw 190 was purchased

shortly after this story ends.

For these reasons I have

chosen to accept the RLM version of the story

largely at face value; that the production problems with the DB series of

engines was so acute that all other designs based on the engine were

canceled. At the time the DB 601 engines were being used in both the 109

and 110 aircraft, and Daimler couldn't keep up with those demands alone.

The RLM eventually forbade anyone but

Messerschmitt to receive any DB 601's, leading to the shelving of many

designs from a number of vendors. After all, the 109 and 110 were better

than anything out there, so another plane that was even better

didn't seem important at all.

The only option open to

Heinkel was a switch to another engine, and the RLM

expressed some interest in purchasing such a version. At the tim the only

other useful inline was the (inferior) Junkers Jumo 211, and even that was

in short supply. However the design of the He 100 made adaptation to the

211 difficult. Both the cooling system and the engine mounts were designed

for the 601, and a switch to the 211 would have required a redesign.

Heinkel felt it wasn't worth the effort considering the plane would end up

with inferior performance, and so the He 100 production ends on that sour

note.

For this reason more than

any other the Fw 190 became the next great plane of the Luftwaffe, as it

was based around the otherwise unused BMW 139 (and later BMW801) radial

engine. Although production of the engines was only starting, the lines

for the airframes and planes could be geared up in parallel without

interrupting production of any existing design. And that's exactly what

happened.

Notes

Another chapter about the

operational use of the He 100 is referred to in Len Deighton's fictional

work Bomber. In the book he tells the story of an RAF

Mosquito pathfinder/marker being shot down by a nitrous-oxide (GM-1

presumably) equipped He 100. The use of laughing gas on the Heinkel

suggested the plane's nickname, the plane was referred to as the "he he".

This account entirely fictional, but still, one wonders where the idea

came from.

[A reader noted that in

his version of the book the plane in question is a Ju 88S. My recollection

might be faulty. Interestingly the 88S was a bomber-only version, and

could not have been used in this role!]

There is some disagreement

on various measures depending on the source, this appears to be due to the

limited number of records left for the plane. Common disagreements are on

the service ceiling, and the empty weight is also often listed at 1810kg

(3,990lb). Another issue is the overall height of the plane which is

sometimes listed at 2.5m. I believe this is in error in this case, the

other common figure of 3.6m is used because that is likely correct for the

enlarged tail of the D-1 models.

Most importantly it should

be noted that almost all of the planes underwent engine modifications and

tweaking during their lifespan. The 650km/h speed is almost universally

quoted for the D-1 models, but it may be the case that this is the speed

of the earlier and more slippery V4 "A" model.

After reading the earlier

versions of this article, a number of people expressed their concerns with

this figure, and suggested further research. In the meantime it is quite

likely that the AIR 40/237 number in the 390mph range is accurate for the

production plane.

All measures and

performance data in the table are for the D-1 production model, and taken

from the primary source listed in the Sources section. I have used metric

values as the primary form of measurement in most cases, with the

exception of engine power. This might seem arbitrary, but it appears this

is the way most people prefer to see them. Conversions for power use 1 hp

= 550 ft.lbs/s = 745.6W.

|